Peter Paul Rubens, “The Hermit and Sleeping Angelica”

Oct 10th, 2018 by JGB

Inadequacy in “Under a Certain Little Star”

Oct 10th, 2018 by snyder20

Szymborska writes in a pointed, direct style that is lyrical at the same time. Some of her poems, like “Reality Demands” and “The End and the Beginning,” discuss events from World War II. Out of all the poems in these selected works, “Under a Certain Little Star” is my favorite. The whole poem speaks to a feeling of inadequacy, a universal sentiment that everyone has felt at some point or another. By including the words “Certain Little” in the title, Syzmborska indicates to the reader how small and insignificant and alone the speaker feels. Specifying the sun in this manner makes it sound isolated, as if the narrator, and not 7.53 billion other people, is the only one illuminated by its light.

In the poem, Syzmborska apologizes to trees, concepts, and events for not being enough. While there is something whimsical about her asking hope to forgive her laughter, or “the cut-down tree for the table’s four legs,” there is an unbearable sadness to the poem. The line “I myself am an obstacle to myself” is particularly heartbreaking. I am amazed by the quality of these translated poems, “Under a Certain Little Star” included. The translators did a fantastic job of maintaining the original tone of the poem (I’m assuming here since I don’t speak Polish) and making sure that it stayed consistent.

The Familiarity of “Unexpected Meeting”

Oct 9th, 2018 by asnyder20

I loved Wislawa Szymborska’s poems. She is a very subtle writer, and it’s amazing to me that her work was translated from Polish to English so successfully. I particularly liked her poem “Unexpected Meeting,” and the way she utilized imagery to say something about what her characters were feeling without ever explicitly saying so. “Our hawks walk on the ground. Our sharks drown in water. Our wolves yawn in front of the open cage,” she writes, creating a sense of wrongness without ever saying it outright. Even people who do not spend much time with these animals know that it is not likely for a hawk to walk rather than fly, or a shark to drown in water, or a wolf to not run out of an enclosure at its first chance of freedom. This whole poem is about a very short exchange, where two acquaintances meet unexpectedly and do not know what to say to each other. This is a scenario that every person has experienced at some point in their life, but, in just thirteen short lines, Szymborska has expressed the deep awkwardness of that situation in a completely honest and unique way.

I’m curious about the history between these two people. Are they estranged friends? Were they in a romantic relationship that fizzled out? The lines “We treat each other with exceeding courtesy; we say, it’s great to see you after all these years,” make me believe that, whatever their relationship was and however it ended, it was painful and difficult for both of them.

Son, You’re The Angel Of Darkness

Oct 8th, 2018 by rhoades20

Rhoades, Ailish

October 6th 2018

Contemporary International Writers

Son, You’re the Angel of Death

I snuck out of the house early, just as the sun was peeping over the mountains behind my house. I brought my little sister Charlie with me, to see the chickens. Chickens were the only thing that could make Charlie laugh these days, since Daddy ran off. Charlie was Daddy’s girl, he always used to bring her out to the barn in the morning, swinging a metal pail behind him to put the eggs they collected in. That was her job, to collect the eggs so Mama could make breakfast for us after chores were done. Daddy used to pick up the chickens and pretend to make them fly towards her head, that always made her shriek with laughter. Mama didn’t like us going out to see the chickens before church, but Charlie had looked so sad and I wanted to make her feel better. I just wanted to make her feel better. When she was done collecting the eggs, I picked up our sweetest hen, her name was Hen-rietta, and ran towards Charlie while making airplane noises. I thought I was doing it right, but I scared her and she dropped the pail and I heard the cracking of eggshells. Charlie started crying and Mama must have heard because she came running out in her nightgown and curlers. She scooped up Charlie with one hand, and smacked me across the face with the other. She didn’t say a single word.

I gathered up the eggs that hadn’t broken and walked back to the house, head hung low. I just want to help, Mama and Charlie have been so sad since Daddy left, I just want to help. As I was walking up the front steps of our wide front porch, I noticed our neighbor Jimmy sitting in the old rocking chair next to the door. He rose slowly, careful not to drop the Bible in his left hand, grabbing my arm as I walked up to him with his right. “Your Mama is going through enough without you causing trouble young man. You do as you’re told and that’s it. I always told your Daddy you were the angel of death.” Shaking his head, “Sure is a shame.” My shoulders hunched I walked through the front door, my mood bluer than the flowers on the wallpaper in our kitchen. I just want to help. I stood on the stepstool and grabbed the big mixing bowl off the top shelf, and the wire whisk out of the ceramic vase by the sink. I heated up the skillet and cracked the eggs into the bowl, whisking them up with a little milk, just how Mama likes them. I scrambled them in the skillet, then put the leftover bacon from the morning before on plates with the eggs.

Mama and Charlie came down the stairs, freshly showered and dressed in their Sunday best. Mama scowled when she saw the plates on the table. “You’re supposed to be a man Jacob. You shouldn’t be cooking breakfast. After church you’re helping Jimmy and Pastor George in the garage. The tractors acting up again and it’s time for you to start earning your keep around here. Go get washed up.” My eyes felt hot with tears as I turned away and walked upstairs to get changed.

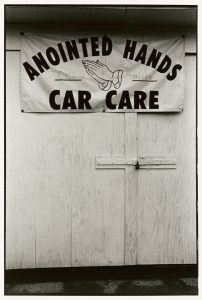

After the service Mama walked me over to the church garage, the sign reading “Anointed Hands Car Care” hung over the wooden barn doors at the entrance. I thought it was strange seeing the two men, with their white shirt sleeves rolled up to their elbows, and the line of grease ending right below. I don’t know anything about tractors, I know I’m just getting in the way. I just want to help, but I have never been very good with mechanics. I like to be in the kitchen, or with the animals on the farm, but if this is what Mama needs of me, I guess this is where I’ll be. I roll up the sleeves of my blue striped button down, just like Pastor George, and walk over to the other men.

On the long walk back home, I let the tears roll down my face. Jimmy’s words pounded in my head like the hammer Pastor George used on the tractors big wheels, “You’re the angel of darkness son.” Daddy was the one who left, I just wanted to help Mama and Charlie. I try to make them smile, make Mama’s life a little easier, but I still just get in the way. Maybe I am the angel of darkness. As if to confirm my thoughts, a shiny black crow flew over my head and landed on my shoulder. It stared me right in the eye as I stopped dead in my tracks, horrified. The tears stopped flowing as I stared back into his beady little eyes. He seemed to be egging me on, daring me to make him leave. “Well Mr. Crow, at least I have you to keep me company. You might just be my only friend now.” I began walking again, tense with the anticipation of the crows departure from my shoulder, but was surprised when he stayed perched. As I walked, two more crows started flapping around my head before settling on either arm. The omen is clear as day, I am the angel of darkness, “Thank you Lord, I understand. I am a burden. I am darkness. What do I do now? Where do I go? Why was it Daddy who left, should it have been me?” I screeched up to the heavens, all the while the crows stared up at me with their cold, judgemental eyes. I began flapping my arms, begging them to leave me be.

I began running, pumping my arms hard the crows flew off, the sound of them squacking filled the air. I didn’t stop pumping until I had flung myself up the three steps to the front door. Shoving open the screen door I raced into my room, falling to the bed gasping for air. Whether I was choking from the run, or from my tears I was unsure. I heard the door open softly behind me, and sat up when I felt a little hand on my shoulder. Charlie cautiously climbed up onto my bed, sitting facing me. I turned to face the door she had just walked in through, until I felt her place both hands on either side of my face and turn me to face her. “Thank you for breakfast Jakey. The eggs tasted like sunshine. You’re my sunshine Jakey.” I looked at her little girl face, the chubby cheeks and the pink ribbons in her pigtails. You are my sunshine was our favorite song when we were really little, we used to run around the yard singing it at the top of our lungs to each other. “You’re my sunshine too Charlie.” She grabbed my hand and hopped off the bed. I followed her down the stairs and out the screen door, back to the coop where the chickens lived. “Can you make them fly Jakey?” I picked Hen-rietta up off the grass, and made my most believable airplane noise, swinging Hen-rietta around. Charlie’s laughter filled the air like music, swirling up past the crows, and up to the heavens. I must have swung Hen-rietta a little too hard because I felt her go limp in my hands, dead weight. The angel of darkness has struck again.

Analysis of Selected Wislawa Szymborska Poems

Oct 5th, 2018 by rossi21

In “Unexpected Meeting”, Szymborska marvels at the simplicity of the animal kingdom. This simplicity is reflected in the shortness of the sentences: “Our tigers drink milk. Our hawks walk on the ground. Our sharks drown in water. Our wolves yawn in front of the open cage.” (Szymborska 137). In the preceding couplet, she acknowledges how less simple mankind is, how we often present false versions of ourselves to others or act in a way that is the opposite of what we are feeling, as opposed to animals: “We are very polite to each other, insist it’s nice meeting after all these years.” (Szymborska 137). The final stanza reflects the apathy felt by the poem’s two subjects towards their own species, thinking them to be far below animals, who are simple and true and extraordinary in so many ways, unlike humans: “We fall silent in mid-phrase, smiling beyond salvation. Our people have nothing to say.” (Szymborksa 137).

In “The Women of Rubens”, Szymborska writes about the subjects of Peter Paul Rubens’s paintings, a 15th century Flemish artist known for his depictions of full-figured women. It is interesting to see how Szymborska celebrates nonconventional body types just as Rubens does, assuring her readers that just because they don’t look like other women doesn’t mean that they are ugly or imperfect: “For even the sky is convex, convex the angels and convex the god—mustachioed Phoebus who on a sweaty mount rides into the seething alcove.” (Szymborska 139). Her descriptions of slimmer women are also worth mentioning; at times, it almost seems as if she is making criticisms towards them, comparing them to birds: “Their ribs all showing, their feet and hands of birdlike nature. Trying to take wing on bony shoulder blades.” (Szymborska 139). The second to last stanza demonstrates the ways in which trends fall in and out of fashion: “The thirteenth century would have given them a golden background, the twentieth—a silver screen. The seventeenth had nothing for the flat of chest.” (Szymborska 139). In the wake of this changed (or changing) attitude towards full-figured women, Szymborska celebrates them, heaping praise upon them: “O meloned, O excessive ones, doubled by the flinging off of shifts, trebled by the violence of posture, you lavish dishes of love!” (Szymborska 138).

In “Pieta”, a reporter seeks out the mother of a man who was killed, bombarding her with questions about her now-famous son’s life and death, which she answers. Right away, we are able to see that this is nothing new to the mother, that she has long since become used to such intrusions, and that she is ready for anything the reporter may have to ask her: “She holds herself erect, hair combed straight, eyes clear.” (Szymborska 139). The insensitive nature of the reporter is reflected in the answers given by the mother to their questions: “Yes, she was standing by the prison wall then…Regretting not bringing a tape recorder and movie camera. Yes, she knows what those things are.” (Szymborska 139). The mother’s pain is evident as she recalls the aftermath of her son’s death: “On the radio she had read his last letter. On the television she had sung old lullabies. Once she had even acted in a film, staring into the klieg lights till the tears came. Yes, she is moved by the memory. Yes, she’s a little tired. Yes, it will pass.” (Szymborska 139). We especially feel for the mother in the final two lines of the poem, knowing that she is being forced to relive her trauma again and again with each new person who comes to seek her out: “Getting up. Expressing thanks. Saying goodbye. Going out, walking past the next batch of tourists.” (Szymborska 140).

In “Theater Impressions”, the narrator (perhaps Szymborska) informs us of her love for the endings of tragic plays. A few lines that really stood out to me in this poem were, “The trampling of eternity with the tip of a golden slipper.” (Szymborska 140) and “Bows solo and ensemble: the white hand on the heart’s wound, the curtsey of the lady suicide, the nodding of the lopped-off head.” (Szymborska 140). I found the last stanza to be especially relatable, as I have often felt the same sadness when finishing a book or a film, wishing that it did not have to end: “But truly elevating is the lowering of the curtain, and that which can still be glimpsed beneath it: here one hand hastily reaches for a flower, there a second snatches up a dropped sword. Only then does a third, invisible, perform its duty: it clutches at my throat.” (Szymborska 141).

In “Under a Certain Little Star”—my personal favorite of the collection—we are treated to an examination of one’s perceived faults. I really resonated with this poem when I read it; it made me remember when I had similar ideas about myself when I was younger, focusing so much of my energy on my own perceived faults, no matter how small they might be. Lines such as “Forgive me, far-off wars, for bringing flowers home.” (Szymborska 141) and “I apologize to everyone that I cannot be every man and woman.” (Szymborska 141) are so applicable to moments in my life where I considered myself to be at fault for the smallest, most indirect of things/problems. This is a poem that I believe everyone should read, because, without a doubt, everyone has felt like this at some point in their lives. Though they may not always be aware that other people feel or have felt the same way, I believe that this poem, as it did for me, could help to clue more readers in on the fact that no one is perfect, that you are not to blame for every little problem, and that, similarly, you cannot fix everything that is wrong with the world; you just have to live your life. The poem’s title is also interesting to consider. Could the “certain little star” be referring to the sun? Could an overarching theme of this poem be the reality of everyone living on Earth—all of the problems that we face, all of the questions that we ponder, and all of the personal struggles that we battle within ourselves?

In “Reality Demands”, we are reminded of the everyday tragedy of reality, but also that in the face of all these tragedies, life continues on. Mostly, the poem serves as a reminder that we must live in the present, no matter what we have faced in the past: “Letters fly back and forth between Pearl Harbor and Hastings…” (Szymborska 142); “On tragic mountain passes the wind rips hats from unwitting heads, and we can’t help laughing at that.” (Szymborska 143). The haunting possibility that every inch of the world has been touched by tragedy at some point in time really stuck with me: “Perhaps all fields are battlefields, all grounds are battlegrounds, those we remember and those that are forgotten.” (Szymborska 143). I also really enjoyed, “There is so much Everything that Nothing is hidden quite nicely.” (Szymborska 142). I think that this could definitely be considered a timeless poem; no matter how bright our future may be, the possibility of tragedy always exists, and this poem serves as a great reminder that no matter what, we must, and do, go on.

In “The End and the Beginning”, we glimpse the details of the aftermath of war, as well as how the memory of the event in the minds of the witnesses inevitably fades over time with the coming of future generations. The stanzas depicting the post-battle cleanups are especially haunting: “Someone’s got to shove the rubble to the roadsides so the carts loaded with corpses can get by.” (Szymborska 144); “Someone’s got to trudge through sludge and ashes, through the sofa springs, the shards of glass, the bloody rags.” (Szymborska 144); “Someone’s got to lug the post to prop the wall, someone’s got to glaze the window, set the door in its frame.” (Szymborska 144). Perhaps even more heartbreaking than that is the acknowledgement of how, eventually, all memory of the tragedy will be forgotten: “Those who knew what this was all about must make way for those who know little. And less than that. And at last nothing less than nothing.” (Szymborska 145). This also ties in nicely with the preceding poem “Reality Demands”, which acknowledges that life and time will always move forward, no matter what horrible things unfold each day.

The Dwarf and His Obsessions in ‘The Keeper of Virgins’

Oct 4th, 2018 by rhoades20

I really enjoyed this story, and the character crafted by Al-Shaykh. The dwarf, as he is referred to throughout the entirety of this story is a very unique and misunderstood man. All he wants is to become a part of the convent, which at first I believe is very honorable and pure of him, but by the end I begin to question his motives and the obsessiveness in his behaviors. I completely understand how someone can latch onto something and let it become their entire life, and manipulate the entirety of their thoughts, but I feel as though the dwarf has taken it to an unhealthy level. I believe that he has some psychological issues that are causing him to become paranoid in regards to the occupants. For example, when he believes that the convent’s occupants and even his own family are in cahoots to lie to him, that screams red flag at me. In the very beginning, much as Amber said, I thought that he was a very innocent and pure man whom I felt very badly for. By the end though his character leaves a bad taste in my mouth, he makes me feel a little unsettled because I feel that he is not as pure as we thought and has a much deeper issue going on. That being said, I liked the development of his character to a sweet innocent man whom we take pity on, into this character that we begin to question and re-evaluate by the end. The route the author took to get there is very successful in my opinion, and flowed with the action of the story.

Perspective in “I Sweep the Sun off the Rooftops” and “Keeper of the Virgins”

Oct 4th, 2018 by tuite20

In “I Sweep the Sun off Rooftops,” author Hanan al-Shaykh illustrates the desire of travel for the main character, which is unusual due to where she is from. While the narrative goes on, we learn more about others warning her about life outside Morocco but can infer that she might have made the sacrifice to travel for a bigger reason, as she tells us that she is in charge of herself in England. While the English man longs to be in Morocco and wants to leave, the main character is more aware of the misfortune in Morocco, just as the English man is more aware of the misfortune in England.

In “Keeper of the Virgins” the dwarf longs to belong somewhere. Thus, when he enters the convent the perspective others have of him change. The people who live outside the convent criticize him and cast him to the side, while the nuns in the convent believe that he is a “gift from God.” When his mother and brother plead for him to come back, he decides against it, now that the dwarf has more perspective on what love should be, versus the love he received outside the convent.

Contrasting Devotions in “The Keeper of Virgins”

Oct 4th, 2018 by byrd19

They were eaten up heart and soul with their love for Christ. This was true love, the like of which he had never found in any novel, translated or otherwise. Never before had he encountered such passion and devotion. Was this what they called sacrifice? The dwarf checked himself. Of course. They had sacrificed the world and their families for the sake of this love, or for the sake of competing for this love.

– Ḥannan al-Shaykh, the Keeper of the Virgins

In The Keeper of Virgins, Hanan Al-Shaykh contrasts two very different types of devotion as she follows the journey of the main character from being what seems like a spurned lover to a devoted aid in a convent. At the beginning of the story, we see the man resolutely walking 4 hours every day in order to wait in front of the convent for the chance to speak to Georgette. His demeanor during this section of the story is very determined if not somewhat aggressive. He becomes suspicious of the workers and feels betrayed when he discovers the gates open at night when he is not there to see or enter them. His fixation with Georgette and, eventually the exclusivity of the convent itself feels obsessive and almost selfish as his intent doesn’t seem to be to show or give love but to selfishly take.

The dwarf’s devotion transforms towards the end of the story when he becomes a devoted aid to the nuns. As he observes their selfless allegiance to their religion it seems that he is transformed within himself. He no longer seems to be fixated on Georgette but to the nuns as a whole. It is in the convent that he seems to really discover the “true love,” he had been desperately seeking. He commits himself to help them in every way without expecting anything in return. In a way, his devotion becomes pure when he witnesses the selflessly unwavering intensity of theirs.

Leila Chatti, “Motherland”

Oct 4th, 2018 by JGB

What kind of world will we leave

__________for our mothers? My mother

calls me, weeping. I am

__________far and the country she gave

me could kill me. Or

__________that’s what she’s saying, her voice

clumsy with tears—my mother

__________who never cries, and so

for this, too, apologizes. Sometimes, more

__________often, I want to mother

my mother. I’ve begun to

__________wonder what it is like for her

to have four hearts

__________outside her body, buried

in brown and fragile skin. I never wanted this

__________for my children, my mother sobs

from a Michigan town

__________where once men crowded in white

cloaks, their sons still

__________there lingering at drug stores and gas pumps

with steely guns and colder eyes.

__________What do you tell a mother

you love too much

__________to lie to? My mother

named me Leila because it was a song

__________white men played on air guitars, which meant,

she’d hoped, they couldn’t hate me. I’m so scared now

__________for Rachid, even with his blonde hair—

My mother thought her blood

__________might protect us in this country

from this country, her fair genes and castaside

__________Catholic god. Thinks now

she failed us as children because she only ever told us

__________stories of monsters

we wouldn’t recognize. Mother,

__________I know these men

could be your brothers

__________and do not blame you. She weeps.

I am far and the country

__________monstrous. What kind of world

do we mother, knowing

__________what it is, what it’s capable of?

The long night stretches

__________between her window and mine.

As if comforting a child, I say the word

__________kind—as in, the world is still

kinder than we think. I think

__________I believe it. Mom I say

stop crying—no one’s leaving this world

__________to anyone yet.

Questioning Georgette

Oct 4th, 2018 by snyder20

Hanan al-Shaykh’s “The Keeper of Virgins” centers around an unnamed dwarf narrator who is trying to gain access to a convent. A young woman named Georgette has recently become a member of the convent and the dwarf wants to find her, which is why he is so fixated on joining it. It is implied that the narrator has romantic feelings for Georgette that she does not reciprocate, as she refuses to see him on his daily visits.

I think a lot of things about this story went over my head, and Georgette is one of them. Did she die before the dwarf got his watchman job at the convent? That would explain why he never sees her, even though the convent is small, and the nuns never leave. He says that the nuns all look the same, but I think that he wouldn’t have trouble recognizing someone who has had that profound of an influence on his life. The head nun also shows the dwarf a rotting corpse. I couldn’t tell from the prose if this is her trying to make him let go of Georgette or show him that he will be with the convent for the rest of his life.

Obsessiveness in “The Keeper of the Virgins”

Oct 4th, 2018 by asnyder20

This story first appealed to me because of its simplicity, but my interest in it deepened as I took notice of some of its deeper elements. “The dwarf,” as the protagonist is called, appears to be a simple character. His one desire at the beginning of the story is to enter the convent, which has thus far refused to open its doors to him. Once inside, he immediately agrees to work there and is in awe of the nuns’ devotion to their religion. He seems to have very pure intentions, as well, even expressing the desire to “snatch the washing out of the boiling water to save them from having to do it” (Al-Shaykh 13). He looks up to the nuns, rather than viewing them with the baser intentions that one might expect of a man who tries obsessively to enter a convent.

However, there is one aspect of the dwarf’s character that prevents me from seeing him as a completely pure and good person. He is obsessive in his interest in the convent and its occupants, and even goes as far as to believe that “everybody [has] joined forces to concoct a lie about the existence of this convent … they were all lying to him” (10). His irrational thoughts do not stop at strangers, though: he even thinks that his own family is deceiving him. An additional point that belies his obsessive tendencies is the presence, or lack of, the character Georgette. We do not know anything about her other than that the dwarf knows her, and that she has joined the convent, but the dwarf is very interested in finding her within the ranks of nuns. It is hard to tell why he wants so badly to see her. Is he in love with her? Were they friends? Was she one of the few people in their world who was kind to him?

I want to like this story: it is well-written and possesses a gentle simplicity that I have not encountered in any of the other readings for this class. However, I cannot enjoy it as much as I would like, as the main character is vaguely unsettling in his obsessive habits.

Cultural differences and Sexuality in “I Sweep the Sun off Rooftops by Hanan al-Shaykh

Oct 4th, 2018 by peterson20

“I didn’t chew my fingers with regret at giving him my virginity, furious at my weakness in lying down for him, and taking this boy in my arms just because he was English, a citizen of that great nation which had once ruled half the globe; nor did I blame myself for having clung to the notion that I had severed all links with my country just because I had traveled to London alone without any member of my family. Instead of striking his face and grieving aloud because my hymen was no longer intact, I wondered, is it because he’s an Englishman that he doesn’t feel proud he’s taken my virginity, or is he frightened that now I’ll try to force him to marry me?”

In “I Sweep the Sun off Rooftops,” we know our narrator is from Morocco and not from England, which is where this story takes place so we can assume there is a culture difference. In this paragraph, our narrator gives some specific details of how she isn’t acting, which seems out of place for any story, but feels like a right choice for this one. Usually, in stories, we get what the character did do, which shows that this is important and the reader pays attention to the details. We can tell by how much the narrator tells us what she didn’t do that this is a way she was raised, that she should feel ashamed and angry for having sex. The fact that she doesn’t do this gives the readers the impression that she either doesn’t care or that now that she is away from Morocco that she doesn’t have to follow those social norms. This is significant because she doesn’t seem to have any trouble keeping that social norm at bay, while later in the story she keeps parts of her culture still in her head. One example is, “How would the English boy go on living now that he’d been found out?” In our narrator’s culture, LGBT+ is not tolerated. There was a man she knew who committed suicide because people suspected him of having a relationship with someone of the same gender. So our narrator keeps parts of her culture close to her heart, but things that referred to her own sexuality and her own sexual experiences she doesn’t seem to carry with her as much.

The Outsider in “The Keeper of the Virgins” & “I Swept the Sun off Rooftops”

Oct 3rd, 2018 by currin19

In “The Keeper of the Virgins” and “I Swept the Sun off Rooftops,” Hanan al-Shaykh deals with the outsider. Both of these characters are either outsiders in a different country or outsiders in their own culture. In “The Keeper of Virgins,” the dwarf believes he does not belong anywhere but the convent where he spends his days outside of the gate reading. It is not until the dwarf achieves his goal of entering the convent that he finally feels like he is home. The people in the “outside world” criticize him and cast him to the side, while the nuns in the convent say he is a “gift from god.” The outsider in “The Keeper of the Virgins” is isolated in his own culture and longs for something different, on the other hand, in “I Swept the Sun off Rooftops,” a woman is lost in the culture of a different place. In both of these stories al-Shaykh wrestles with similar themes: being and outsider and living in a culture different than your own.

The woman in the story is living in London, having moved from Morocco. Unlike the dwarf in al-Shaykh’s other story, the woman in “I Swept the Sun off Rooftops,” comes to accept her new world. Even after walking in on her “lover” with a man and coming to the realization that she has been tricked, the woman in “I Swept the Sun off Rooftops” values her freedom and independence. She says, “I was happy in London, free, mistress of my self and my pocket.” This is a different type of freedom than in “The Keeper of the Virgins,” but it is also very similar. Both of these characters find solace in cultures quite opposite of their own. They may be outsiders but at least they are free.

Language in “The Keeper of the Virgins”

Oct 3rd, 2018 by bell20

In her “The Keeping of the Virgins”, Hanan Al-Shaykh uses language beautifully to immerse the reader into the story. There are many lovely descriptions in this body of work, both in rhythm and imagery. “They had grown used to seeing him every morning shortly after they set to work, bending over the hibiscus bushes to gather the wine-colored blossoms. He would go by with a confident step, heading for the convent, where the pure ones lived, books and magazines tucked under his arm, a cloth bundle containing his food for the day held firmly in his hand.” The descriptions in these sentences, paired with the author’s intelligent verb choice, make them very pleasant to read.

There is also a purity in this piece, obviously derived from the title and subject matter, but also in the writing. One of the very last paragraphs discusses the dwarf’s love and devotion to the nuns, and though it is written very delicately, it also reads as being very holy. “They were eaten up heart and soul with their love for Christ. This was true love, the like of which he had never found in any novel, translated or otherwise. Never before had he encountered such passion and devotion. Was this what they called sacrifice?… He’d make their mud-brick beds for them and be close to their sheets–for Christ must smell that they were clean.” The innocence in the women shines in this paragraph, but so does the love the dwarf feels for them. For much of the story, the reader comes to know of how the people around the dwarf feel about him; he is an outcast. But in the convent, with these virgins that he has come to look over, he is accepted and valued.

The Orientalist myth and metaphor in “I sweep the Sun Off Rooftops” by Hanan al-Shakyh

Oct 3rd, 2018 by cmahsas

After eating a piece of chicken dipped in cumin and saffron, which he seemed to have liked, he asked me where I came from. I told him and it was as if I’d opened Heaven’s door. His face softened, his pupils grew bigger, and his irises went deep green like olive oil. Enthusiastically he told me that he’d always wanted to visit Marocco, live there even, and that our hashish was the best of all.

In his short story, I sweep the Sun Off Rooftops, Hanan al-Shakyh uses the Orientalist myth and the metaphor to structure either the narrative or the poetics of this one.

Indeed, the Orientalist myth is defined by Edward Saïd as a misinterpretation of the Orient as a source of fantasms. We can see in the extract that is emphasized in this post that the “English guy” is associating Marocco, which is a country from the Maghreb, to good hashish and to what he thinks this country is. The fact that the narrator’s origins are reduced in this text to a potential resource from her country, and also to her incapacity to speak in English in some situations is significant. But, her way to describe the English boy or her new country, for example, is also a part of the Orientalist Myth. She puts the emphasis on his physical characteristics and we don’t have an access to their conversation and don’t even know if they are really able to communicate. She admits herself in the story that she “chooses” him because of his typical English physic. She also distorts the reality because of her prejudices and we can see her disappointment and incomprehension when she understands that he may be gay and using her to have a place where to sleep.

The differences between the two cultures are presented in the text. We have multiple occurrences of the narrator being choked or surprised by some English customs and also not fitting in them. The simplest example is when she feeds the pigeons and says that the neighbors are mad at her because that is not something people can do in London and when she explains what would happen to this same animal if the scene was taking place in her country.

Finally, what shapes this story is the metaphor and the imagery in general. We have a beautiful imagery that also shows the culture shock when it comes to the sun. English persons are craving for the sun and don’t understand why she left a sunny place whereas she says that she can’t do anything with the sun and is craving for goods. The metaphor between the pigeon and the English guy is really poetic and shows her vision of a satisfying relationship. The final line says everything and can be related to the fact she discovered a part she doesn’t appreciate or expected about her English boy.

You’re not beautiful, you’re not white, or even a nice light brown. You’re gray and black like a big rat, but I love you because you’re English and you wait for me every day.

Exercise 2: Patience & Seeing

Oct 2nd, 2018 by JGB

Due Monday, October 8, at midnight: Five stanzas or five paragraphs, in this order:

Thinking of Possibilities in “A Temporary Matter”

Oct 1st, 2018 by amiller20

Throughout this story, the process of connection and separation serves as a key theme. We see this in the distance between Shoba and Shukumar at the beginning and then their slowly growing closer to each other only to separate again when Shoba tells Shukumar that she is leaving him. I do think that the way she tells him she is leaving is cruel, snuggling and cuddling with him to give him hope that things will work out only to drop the bomb that she doesn’t want to stay with him anymore.

However, I wonder if she meant to lead him on like that or if she too was lulled into the hope that they could be like they were before their baby died. I did feel a slight satisfaction that justice had been served when Shukumar told her about the baby, but that was quickly squashed by her reaction. I wonder if things would have been different had Shoba known that Shukumar was there to hold their dead baby. In the end, there was definitely guilt on both sides — Shukumar for not being there for his wife and child and cruelly telling Shoba about their child when she couldn’t bear to hear the details, and Shoba for freezing him out for so long, dragging him through all that hope before destroying it and also feeling that she failed somehow at giving life to their child.

Hope and Mourning in “A Temporary Matter”

Oct 1st, 2018 by minyard20

“A Temporary Matter” by Jhumpa Lahiri is about a couple dealing with the aftermath of the stillbirth of their son. After his death, Shoba and Shukumar find it harder and harder to maintain their relationship, hardly talking except in the safety of a darkened room. At the end of the story, we find out that Shoba has rented an apartment and is planning on moving out. In shock, Shukumar reveals that their baby was a boy and that he had held the baby before the nurses took him away – something he never thought he would tell his wife. The last sentence of the story is a powerful one: “They wept together, for the things they now knew” (630).

The couple does not truly address their mourning until the end, when Shukumar’s words prevent them from ignoring the truth any longer. While this is a sad ending, I also think it is a hopeful one. Throughout the story, Shoba and Shukumar slowly begin revealing secrets to each other, getting to know each other in ways they’d forgotten since the loss of their son. By facing these smaller truths, ones they’d never told each other or admitted aloud at all, they were ultimately preparing themselves to face this truth, even though they did not realize it at the time.

I have heard that most couples split up after the loss of a child, and things are headed in that direction for Shoba and Shukumar. While their decision, of course, is an important one, it is more important that they, both individually and as a couple, face their grief instead of running from it. This secret Shukumar revealed is a harsh one, but it is one that will allow them to mourn and try to move on with their lives. By crying together, they have finally admitted the truth to themselves and can begin to better process the grief they are facing. This, to me, gives the story a note of hope that they will both be able to move on into a healthier place in life.

Solmaz Sharif, “Persistence of Vision: Televised Confession”

Oct 1st, 2018 by JGB

Persistence of Vision: Televised Confession

by Solmaz Sharif

You are like a daughter

to me—the prisoner’s

mother tells me. Meal by

meal she sets then clears. She

rinses some tablewear

the prisoner never

held, then a glass she did,

then recalls her daughter’s

mouth opening softly

to drink water on state-

run TV, then water

over everything. The

glass appears in hundreds

of frames before reaching

the prisoner’s lips. In

between each frame, the grief

our eyes jump to create

movement: dark strips to keep

sharp the glass lip, water

skin trembling, hand that

trembles it. These mothers

move as flipbooks, tiny,

stuttering pasts, sobbing

at the sink. It is death

that sharpens our sight each

sixteenth second, slender,

blocking enough light so

that the prisoner’s face

is again and again

alive each light-punctured

frame, her mouth: in hundreds

of stills is still opening

softly to drink.

About This Poem

“The last time you see your loved one is on TV, giving a forced confession, broken, but you look, maybe, for the loved one you could recognize, who is not broken and reading the state-sponsored script—drinking a glass of water, perhaps. You want to slow this down and replay it. You see if grief itself had a cadence, it would be harshly syllabic—broken, sobbing—a flip book, a slowed down film reel of still frames.”

—Solmaz Sharif

Candlelit Dinners in “A Temporary Matter”

Sep 28th, 2018 by rossi21

They served themselves, stirring the rice with their forks, squinting as they extracted bay leaves and cloves from the stew. Every few minutes Shukumar lit a few more birthday candles and drove them into the soil of the pot. (Lahiri 621)

When we think of candlelit dinners, we normally think of romance, of the beginnings of a relationship. In a way, this is exactly what this dinner scene between Shoba and Shukumar is. Since the death of their son, they have become estranged. They no longer know one another as they used to; they are strangers. With this scene, and with the game Shoba proposes that they play, they slowly begin to know one another in new ways, with each one learning things about the other that they didn’t know before:

‘The first time I was alone in your apartment, I looked in your address book to see if you’d written me in. I think we’d known each other two weeks.’

‘Where was I?’

‘You went to answer the telephone in the other room. It was your mother, and I figured it would be a long call. I wanted to know if you’d promoted me from the margins of your newspaper.’ (Lahiri 623)

Shukumar is also able to suddenly recognize things about Shoba that he has forgotten, that he has stopped noticing since the tragedy and their reduced interactions with one another:

The birthday candles had burned out, but he pictured her face clearly in the dark, the wide tilting eyes, the full grape-toned lips; the fall at age two from her high chair still visible as a comma on her chin. Each day, Shukumar noticed, her beauty, which had once overwhelmed him, seemed to fade. The cosmetics that had seemed superfluous were necessary now, not to improve her but to define her somehow. (Lahiri 624)

This same trend of rediscovery and discovery continues on for the rest of the story, always occurring during a candlelit meal. The darkness emboldens them somehow; they can speak the truth without having to really face the other as it is spoken—almost as if the darkness is a shield. When the power finally comes back on, they have grown considerably closer after this string of candlelit dinners, but one great secret still remains for each of them. When Shoba makes the decision to tell Shukumar hers with the lights on—“‘I want you to see my face when I tell you this,’ she said gently.” (Lahiri 629)—it is because she has grown brave enough during the preceding days to say what she needs to face-to-face; she feels ready enough after all the truths she has told him so far, confident that he will understand her decision because his understanding of who she really is has only grown deeper over the past several days.

As for Shukumar, the little secrets he has told her thus far—cheating on his college exam, ripping out a picture of a woman from a magazine—are nothing compared to what he reveals to her in the story’s final moments: “‘Our baby was a boy,’ he said. ‘His skin was more red than brown. He had black hair on his head. He weighed almost five pounds. His fingers were curled shut, just like yours in the night.’” (Lahiri 630). It is still somewhat unclear to me why Shukumar chose to finally reveal this knowledge to Shoba. Was he simply unable to live with that guilt any longer, especially since the recent rekindling of their love? Did he think that the knowledge would bring her some kind of comfort or closure? Or, did he simply want her to know him in the purest way possible, free of all lies and secrets, before she possibly ended up leaving him forever? Whatever the reason, it makes for one of the most powerful and provocative endings I have ever read. This is an absolutely brilliant story, one that I know will stay with me for a long time. As gut-wrenching as it was, it was an absolute joy to read for its complex characters, beautiful prose, and heartbreaking final scene.

Freedom: Firdaus vs. Mrs. Shin

Sep 27th, 2018 by rhoades20

Freedom in “A Temporary Marriage” & “Woman At Point Zero”

These two stories were very interesting, because of the large parallel drawn in regards to what I feel is the main theme of both, which is the women’s freedom. Although both women crave freedom from the traumatic events they were forced to endure, Firdaus seems much more passionate about escaping and puts up more of a fight. Mrs. Shin however seems to be more afraid (completely understandable) and takes a less intense approach to dealing with her situation.

Firdaus in ‘Woman at Point Zero’ has endured severe physical and emotional trauma that led her to do what she felt was the only way of escaping her pain, which was killing a man and getting imprisoned. She feels that being locked away and sentenced to death is the ultimate escape from her pain. This is heartbreaking that death is more comforting, and the most realistic option for her than anything else. She can not escape her environment and be happy, so why not just go all the way and end her life. At one point in the book Firdaus talks about death like it is something to look forward to, it is a way to gain control in a life where she has never had an ounce of control over any situation. This outlook was so fascinating to me, because despite everything that she has been put through, her outlook is that it all happened so that she could reach her full potential within the universe. Very interesting, and very different than Mrs. Shin’s outlook.

Mrs. Shin has been in an abusive marriage, and when she finally escapes she loses the custody battle for her daughter. When her ex moves him and their daughter to America, Mrs. Shin is forced to figure out how to get to her, and get her out of that atrocious situation. When Mrs. Shin finally finds her daughter and ex, she tells her ex to hit her because no one is watching. Then at the very end we see her cutting herself to release the pain that she has been carrying. I know that Jylian said that this did not make sense to her, but I can understand the logic there. Mrs. Shin, similarly to Firdaus, felt that she had no control over her life and the pain that has been forced upon her. The only way she knows how to gain that control back is to be the one who creates it for herself, that way she is not giving another the chance to hurt her worse than she has herself. When someone is desperate and broken, their logic flips a switch. They do whatever they can, however they can fathom it, to survive and this is what we can see happening here.

Cultural Values in “A Temporary Marriage”

Sep 27th, 2018 by byrd19

When she came downstairs, Mr. Rhee was preparing snail soybean fermented stew and mung-bean pancakes. Mortified to see a man in a kitchen, she tried to wrench the spatula away, when she remembered where she was. This was America, she reasoned, as Mr. Rhee hugged the spatula. Hadn’t she come to live differently? ( Krys Lee, 5)

In “A Temporary Marriage,” Mrs. Shin often finds her own attitude and actions at odds with both American and Korean customs and values. When she enters the US at the very beginning of the story, we see her struggle to adjust to Mr. Shin’s more Americanized way of life when she attempts to wrestle the spatula away from him while he is cooking due to the learned embarrassment of seeing a man carrying out traditionally feminine activities. Later on into the story, it seems that despite the strangely traditional sentiments she expresses, she fully understands the ways in which American culture differs and hopes to capitalize on that in order to see her daughter again. This is seen especially at the moment where she first meets with Detective Kim.

Mrs. Shin had hoped for a second-generation with sloppy Korean, a man raised on hamburgers and fries, someone who might not have crossed the Pacific with his patriarchal ideas intact. Instead, she got Detective Kim. (Krys Lee, 6)

Mrs. Shin realizes that although being a Korean immigrant puts her at a disadvantage in some ways, it also could offer her a certain freedom from the more stringent restraints and patriarchal laws regarding child custody she lived under when still a wife in Seoul. Although her new surroundings seem to exacerbate the self-destructive behavior that has originated from her first husband’s abuse, they also seem to give her a new freedom that she hadn’t experienced before.

Tessa Fontaine: “The Phone of the Wind”

Sep 27th, 2018 by JGB

Tessa Fontaine, who’ll be reading at SBC next week, published this essay in The Believer Magazine. Here’s how the essay begins:

The phone is an old rotary with small holes for your fingers. To make a call, guide your number past zero and once you release, it will carry itself back to where it began. I’d forgotten how easy it was to mess these up. Jerk your finger out too soon, and you’ll never get connected.

The phone sits on a metal shelf inside a glass phone booth in the middle of a lush garden. The shape of your hand holding the receiver is like the shape of your hand holding a bundle of flowers for someone you loved. When I ask Mr. Sasaki why he chose a rotary phone for his phone booth, he says that the extra time it takes to dial is good. Gives you a chance to figure out what to say to the dead.

Most locals come after dark, or very early in the morning. They keep their grief private. If Mr. Sasaki sees someone out in his yard, on the phone, he pretends not to notice.

Death doesn’t end life, Mr. Sasaki tells me. One person dies, and all the others around them go on living.

Life continues.

Life continues, and so Mr. Sasaki has built something to help other people, and himself, continue. It is called The Phone of the Wind.

Tarfia Faizullah, “Apology from a Muslim Orphan”

Sep 27th, 2018 by JGB

Apology from a Muslim Orphan

by Tarfia Faizullah

I know you know

how to shame into obedience

the long chain tethering lawnmower

to fence. And in your garden

are no chrysanthemums, no hem

of lace from the headscarf

I loose for him at my choosing.

Around my throat still twines a thin line

from when, in another life, I was

guillotined. I know you know

how to slap a child across the face

with a sandal.

Forgive me. I love when he tells me to be

the water you siphon into the roots

of your trees. In that life,

I was your enemy and silverleaf.

In this one, the child you struck was me.

About This Poem

“’I write to you across what separates us,’ wrote Czesław Miłosz in ‘To Robert Lowell,’ a poem that is an apology as much as it is an acknowledgment of how elusive understanding can be when we are deeply entrenched inside our own experiences. I was moved by both the vulnerability and irony inherent in Miłosz’s poem, which influenced the writing of ‘Apology from a Muslim Orphan.’”

—Tarfia Faizullah

Freedom in A Temporary Marriage and A Woman At Point Zero

Sep 27th, 2018 by bell20

There are several prominent differences between Mrs. Shin’s character from “A Temporary Marriage” and Firdaus in A Woman At Point Zero, though these differences seem to come together in the two women to make up a common goal of their own sense of freedom. Mrs. Shin claims that she prefers “a world without men,” a statement Firdaus would wholeheartedly agree with, but the former woman seems to rely on them to deliver something that she desperately craves: physical pain and force. When she discovers Mr. Rhee in his room, she “saw that he had been drinking alone, and with her head bowed, her hands clasped behind her, she approached, aroused by the idea of this man out of control.” She goes on to “see a vein in his neck throbbing, and found herself waiting, wanting his harsh, dry lips, his hands tightened around her neck.” These are the first hints given about her desires.

Later, when she is walking through San Julian Park, she says, “It was the other America that had Mr. Rhee trembling, but she stepped off the bus so bored, she welcomed disaster. She strolled around the perimeter of the park, wanting the terrible to happen…” We see the nature of her desires again, once she has tried on Mr. Rhee’s wife’s dress and he finds her, she asks, “How dare you insult me?” and she bows her head, “You should slap me,” she says, “You’re angry…You’ll feel better, after.” And again, later, she tells her ex-husband, “Hit me. No one can see us.” The most disturbing image is the end of the story when she has reached a more emotional point and takes “her sewing scissors and ran them along the back of her thigh. The pain erased all grief, stripping her of camouflage. She was hurtling, she was rapturous, as a wound so bright it looked pasted on, blossomed on her leg… She was becoming herself again in the ardor of the scissors and the flogging belt, loving herself…”

Firdaus, however, states boldly, “I became aware of the fact that I hated men…” (p. 120). At the beginning of her testimony, she says, “However, every single man I did get to know filled me with but one desire: to lift my hand and bring it smashing down on his face. But because I am a woman I have never had the courage to lift my hand. And because I am a prostitute, I hid my fear under layers of makeup” (pp. 13-14). Where Mrs. Shin claims that she would prefer a world without men and then relies on them, somewhat heavily, after becoming attached to them, Firdaus seems almost unable to make that connection with a member of the opposite sex, and extremely comfortable with that fact. At the end of Firdaus’ testimony, she states, “That is why they are afraid and in a hurry to execute me. They do not fear my knife. It is my truth which frightens them. This fearful truth gives me great strength. It protects me from fearing death, or life, or hunger, or nakedness, or destruction. It is this fearful truth which prevents me from fearing the brutality of rulers and policemen” (pg 140).

Both of these women have a similar goal of freedom and release from their male counterparts. Though I do not understand Mrs. Shin’s way of achieving this goal, and I empathize with Firdaus’, I think that in their own way, both women achieved their own kind of freedom by the ends of their stories.